The King’s School gardens are dedicated to Margaret Creighton, the wife of Cuthbert Creighton, who was the Headmaster of King’s from 1919-1936 and 1940-2.

Cuthbert Creighton was born on 26th July 1876 in Worcester, which was where he passed most of his childhood as his father was a Canon of Worcester Cathedral between 1885 and 1891. He married Margaret Bruce on 15th April 1913, when he was thirty-seven. Margaret Bruce had been born in Ravello, Italy, on 23rd August 1881, but was living in London by the time she married Cuthbert.

Margaret gave birth to a son, Tom, in 1916 and another son, Hugh, in 1919. Tom was born in Kensington, London, whereas Hugh was born in Worcester, presumably in their home. For four years the family lived happily in Worcester as Cuthbert was Headmaster of King’s, however tragedy struck on 2nd February 1923 when Margaret died in childbirth along with their third child. She was forty-one years old. Their unfortunate deaths shocked the entire King’s community.

Cuthbert Creighton responded to the shockingly premature death of his wife by buying the remainder of the King’s site (the allotments lying between King’s and the river) from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and laid it out as gardens which he gave to the school. He named them “The Creighton Memorial Gardens” in memory of Margaret Creighton and they were unveiled in 1931.

The gardens remain at King’s to this day in their original location at the side of the River Severn. The main focal point of the gardens is a fountain topped with a small statue of Sabrina, the Goddess of the River Severn.

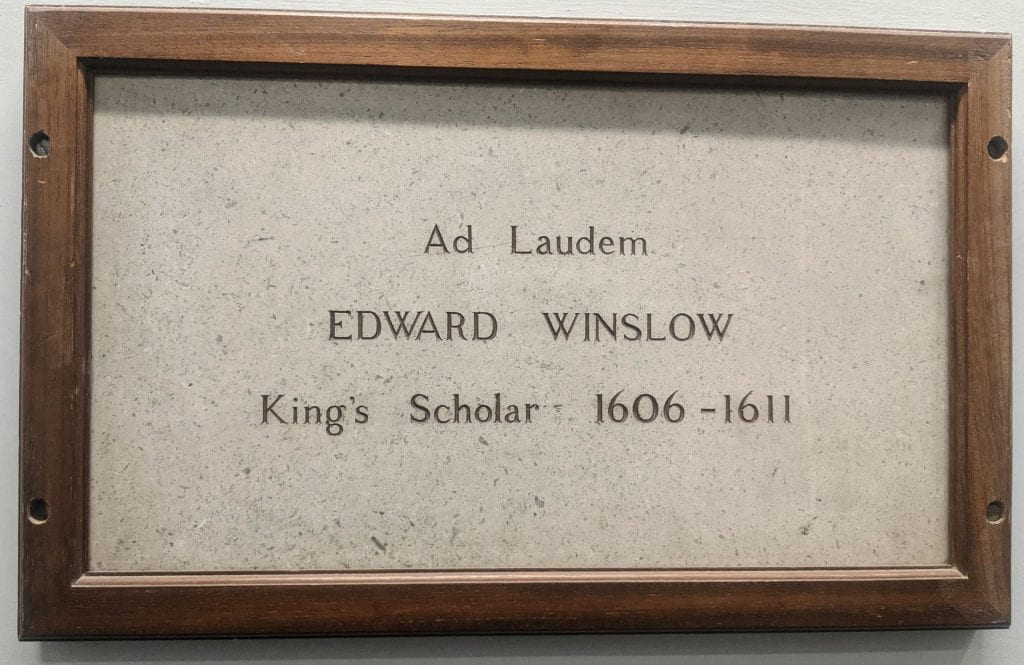

Edward Winslow was born on 18th October 1595 in Droitwich and he was a King’s scholar from 1606 to 1611. During his time at school, King’s was very different to how we know it now. School days lasted for eleven hours and lessons included subjects such as Rhetoric (the study of persuasive speech and writing) and Mythology.

Edward Winslow was born on 18th October 1595 in Droitwich and he was a King’s scholar from 1606 to 1611. During his time at school, King’s was very different to how we know it now. School days lasted for eleven hours and lessons included subjects such as Rhetoric (the study of persuasive speech and writing) and Mythology.